If you’re reading this blog post, it’s likely that you’re also doing bug bounty. Maybe you’re even doing it professionally as a daily job. That’s great, and I envy you, as I could never really get into the idea of becoming a full-time bug bounty hunter. Maybe my past experiences with it, such as hitting the triage wall or long response times, discouraged me from stepping up my bug hunting game.

However, I could not get the idea of having an almost self-sufficient automation that can perform reconnaissance, scan, and report security issues along multiple assets out of my mind. The more important question was whether such an approach would earn its keep or maybe even generate additional income.

Part 1 - Gathering ALL the scope

I must admit that I’m a pretty lazy guy. Don’t get me wrong; I enjoy working in cybersecurity, and I can stare at code for hours to identify bugs. However, after work, I prefer to do other things, such as sport and spending time with friends and family. I don’t think I could spend 10+ hours a day trying to identify issues before other hunters can. So, I thought, “Let’s gather all the assets I can find in my bug bounty programs and start scanning them!” Sounds simple, right? Yeah, I thought so too.

First, I made some assumptions before coding the automation. To minimize the chances of duplicates and reduce the number of assets, I chose to use only private bug bounty programs, as they tend to have more low-hanging fruit–type vulnerabilities that simple automation can find. I also assumed that I would only focus on wildcard scope, meaning that I would only discover and scan the scope presented in *.company.tld. This was necessary to unify the input for the automation, as programs tend to provide assets in a non-unified way. Some provide only certain URLs, while others prefer to use subdomains with wildcards. With the wildcard domain approach, you are also much more likely to avoid OOS (out-of-scope) reports, as it’s usually easy to justify a report for a subdomain in wildcard scope. Keeping this approach in mind, I gathered more than 500 domains from the following platforms:

- Yogosha

- Yeswehack

- Cyberdart

- Intigriti

- Bugcrowd

- Hackerone

- Whitehub

The scope was put into two different files that would act as a flat file database for the automation:

- File

tlds.txtcontaining one domain in one line for reconnaisance input (at the moment of writing I realized that it should be actually called something likedomains.txtbut I used the TLD format for long enough to just stick with it), - File

programs.txtcontaining information about programs and associated domains grouped by the platform. The file is structured in the following format:

[...]

[HACKERONE] Private Company|private-company.com,private-company.net

[BUGCROWD] Foo Corp|foo.com,bar.net

[...]

Well that was easy. We’ve now got all the input that is needed and and it can be just feeded it to the scanner.

Part 2 - Infrastructure dillema

Now, the realization kicked in. How should I approach building the automation itself, so it wouldn’t evolve into one of those never ending projects that you spend more time maintaining rather than actually using. I quickly threw the idea of building an automation platform from scratch, as it would require a lot of trial-and-error before it would eventually start working properly. Instead, a low-code security automation platform caught my attention - Trickest.

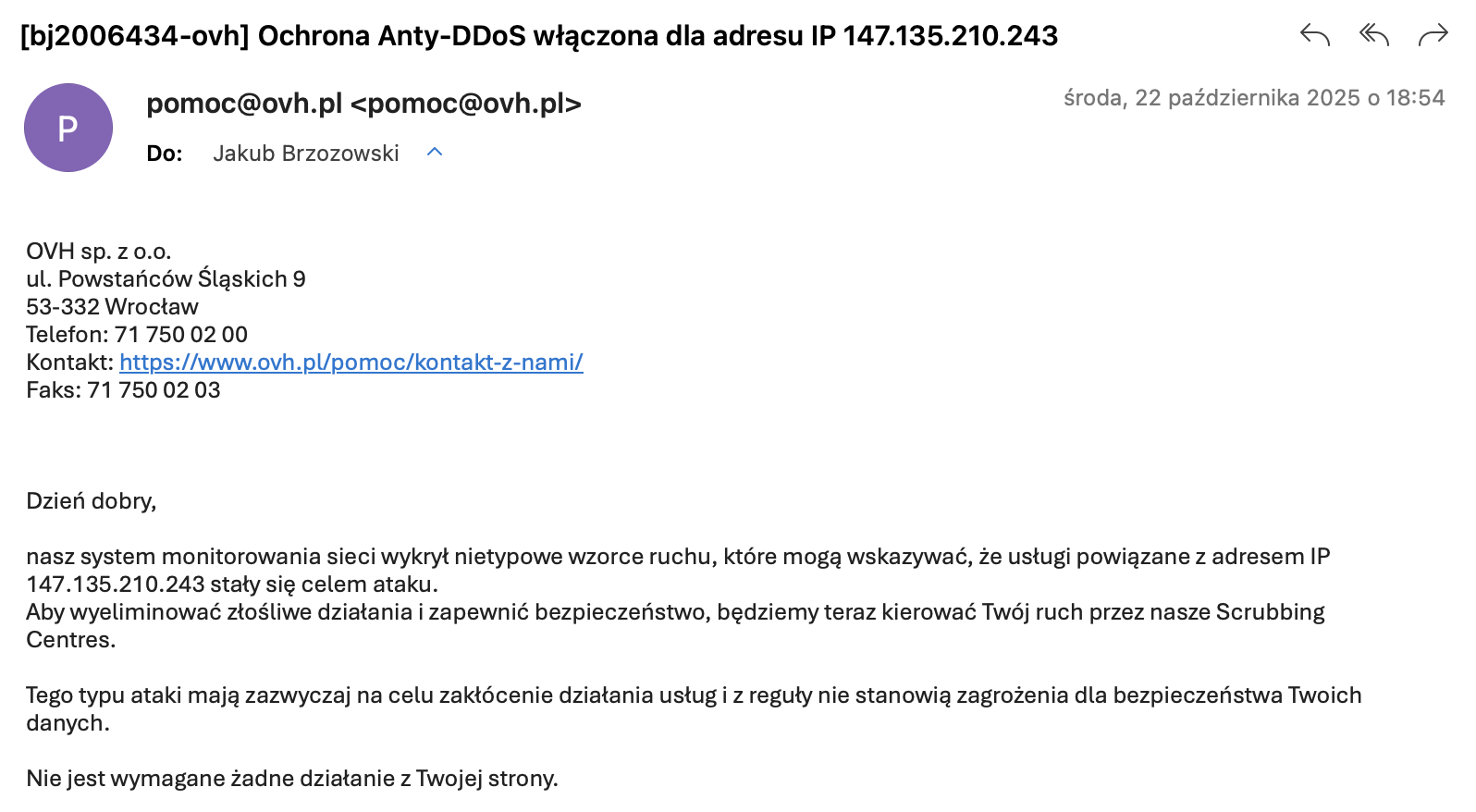

Trickest platform is a modular approach to automation where you can choose between free and paid plans, and even use your own infrastructure to run security workflows. For some time, they even have a self-hosted version. The idea is really simple - you just install a Trickest agent on a VPS, and you are good to go. And as I am a faithful user of OVH cloud services, I chose to buy some servers from them. It turned out not to be the wisest idea because after running a simple subdomain reconnaissance workflow, my server was blacklisted by OVH due to DoS attack 🤡

Message from OVH Cloud saying that UDP traffic originating from my host is triggering their DDoS defences.

Message from OVH Cloud saying that UDP traffic originating from my host is triggering their DDoS defences.

After learning that it is impossible to turn off this “protection”, I wanted to use a VPS from other providers, such as AWS or DigitalOcean; however, their low-cost tier offer was much too pricey for this project to be financially affordable. As I would like to run multithreaded, CPU intensive workflows, I needed a beefy VPS that wouldn’t break the bank. My minimal requirements were:

- 4 core CPU,

- 8 GB RAM,

- 60 GB of fast storage,

- 1 Gbit/s bandwidth,

- 1 TB of monthly traffic throughput,

- <10 EUR per VPS/month

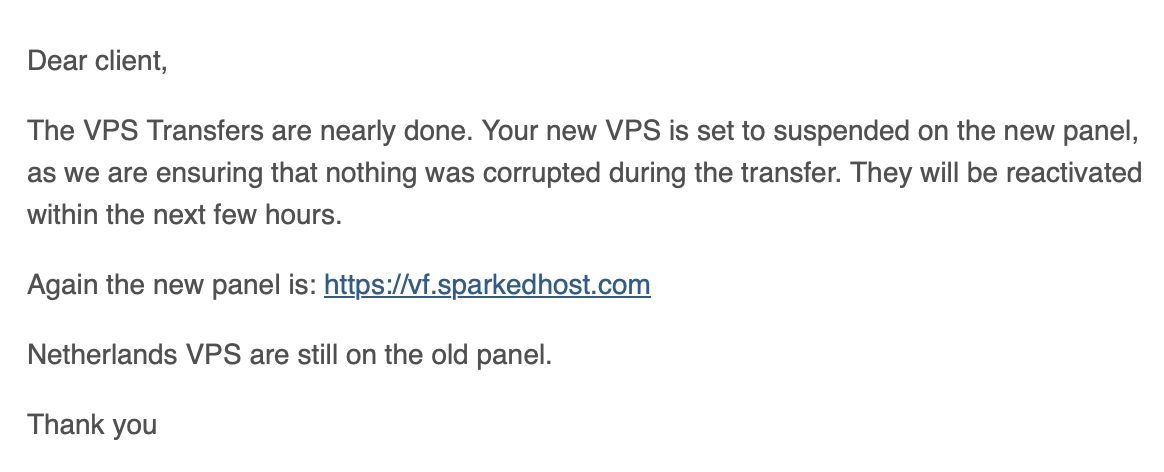

While searching, I found this VPS price tracker website that allows you to compare prices of niche VPS providers. I initially bought 3 servers from Atomic Networks, as it was a killer value of about ~6 USD per VPS/month. Later, it turned out that with cheap VPS providers, you pay twice, as around December, they probably went bankrupt and were acquired by other providers, as whole Chicago datacenter was offline for a few weeks:

Message from Atomic Networks following Chicago VPS outage for several day (how not to do datacenter migration).

Message from Atomic Networks following Chicago VPS outage for several day (how not to do datacenter migration).

Now I am using Layer7 as a provider and I can’t complain about them - the price is slightly higher but at least the servers are in EU datacenter and there were no downtimes so far. In Trickest free tier, you can hook up to 3 external servers and if you want to use their cloud instances as scanning nodes you need to buy running credits which I choose not to do.

Part 3 - Discovering the targets

Now moving on to the automation details. I previously mentioned that the input for the automation will be tlds.txt file containing domains that are considered wildcard scope for bug bounty programs. I needed to construct an automation that will passively enumerate subdomains and check all alive hosts for the returned results. After some trial and error with already defined Trickest workflows and custom tests, I came up with the following flow that gave reasonably good results:

┌─────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Get subdomains.txt │ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ file ├─────►│ │ │ │

│ │ │ subfinder ├─────►│ Send notification │

└─────────────────────────┘ │ │ │ to Telegram channel │

┌─────────────────────────┐ └─────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘

│ provider-config.yaml │ ▲

│ ├──────────────┘

└─────────────────────────┘

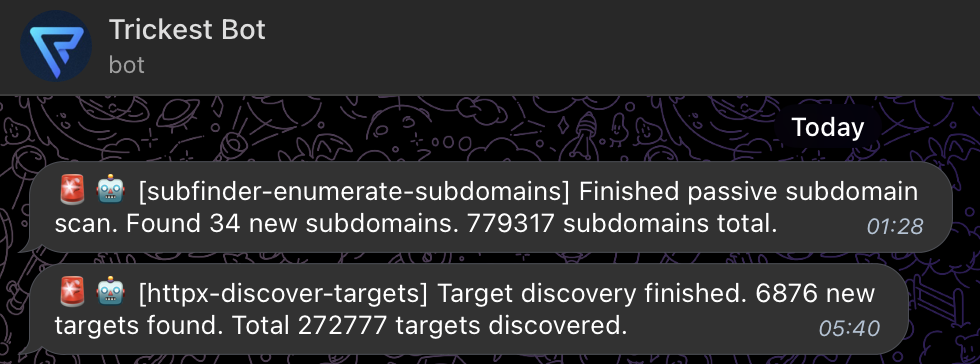

After workflow has finished, a notification with some statistics is sent to the Telegram channel:

Next the automation will check all alive hosts with httpx. I focused only on identyfing alive web ports (80 and 443) since they are most common and also web vulnerabilities are among the most easy to scan in the wild. The workflow is as follows:

┌─────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Get subdomains.txt │ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ file ├─────►│ │ │ │

│ │ │ httpx ├─────►│ targets.txt │

└─────────────────────────┘ │ │ │ │

│ • HTTP/HTTPS│ └─────────────────────┘

│ • Follow │ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ redirects │ │ │

│ • Tech ├─────►│ inventory.json │

│ discovery │ │ (detailed output) │

│ │ │ │

└─────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘

│

│

▼

┌─────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Send notification │

│ to Telegram channel │

│ (host count) │

│ │

└─────────────────────┘

Above workflows are very simplified as I needed to optimize the flow by adjusting host batch count, thread count for httpx and add timeouts to prevent the scans from running endlessly. Usually batches of few thousand hosts and timeout of several seconds worked best for me and tend to yield most accurate results. I have also tried active subdomain enumeration using DNS brute force but such activities cause flood of UDP traffic which often is flagged by providers. Also it was much slower (couple hours vs. minutes) than passive recon and gave only about ~10% results more subdomains with decent wordlist. With this downsides in mind I decided to stick purely to passive subdomain enumeration.

I previously mentioned that target discovery outputs an inventory.json file. This file is a JSON array of identified hosts with the following structure:

{

"timestamp": "2026-01-08T09:29:37.931520029Z",

"hash": {

[...]

},

"port": "443",

"url": "https://target.com:443",

"input": "target.com",

"title": "Welcome to my website!",

"scheme": "https",

"webserver": "Apache",

"content_type": "text/html",

"method": "GET",

"host": "1.3.3.7",

"path": "/",

"time": "70.207238ms",

"a": [

"1.3.3.7",

"1.3.3.8"

],

"tech": [

"HSTS","Cloudflare","Apache"

],

[...]

}

It contains multiple useful fields such as webserver infromation and page title. I find tech field particulary useful as it helps you to search for assets with certain technologies used. This feature shines especially when a certain product is impacted by a 0-day vulnerability like React4Shell. It allows you to quickly idenitfy potenital vulnerable hosts among you asset inventory with a quick grep.

Part 4 - Scanning for vulnerabilities

So I had a working “Target Discovery” workflow that was running 24/7 and was outputting latest list of alive hosts as a candidates to scan. So now let’s just feed them into nuclei, scan and fuzz the targets and report the vulnerabilities. This part was probably the most challenging and the one where I learned that it’s impossible to cover whole attack surface with scanning and fuzzing for every possible vulnerability. With such a large scope 200,000+ hosts and limited resources (3 servers), it’s impossible to run EVERY single vulnerability template for EVERY host. If you schedule such scan you will eventually run out of patience and memory (it’s up to you to choose which would happen first). I decided to analyze this problem scientifically and I came up with different approaches no which vulnerabilities to scan:

- Approach 1 “Common Vulnerabilities” - Identify which vulnerabilities are statistically most common to be reported to bug bounty programs and scan only for them (i.e. directory listings, XSS, backup files, common misconfigurations),

- Approach 2 “Latest Vulnerabilities” - Scan for recently discovered vulnerabilities and new templates,

- Approach 3 “Random Vulnerabilities” - Scan for random vulnerabilities (at least you can only be average with random 😅)

After some optimizations I came up with the following workflow and from time to time I swapped between the approaches:

┌─────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Get targets.txt │ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ file ├─────►│ │ │ │

│ │ │ Split ├─────►│ nuclei │

└─────────────────────────┘ │ into │ │ │

│ batches │ │ • Common vulns │

│ │ │ • Latest vulns │

└─────────────┘ │ • Random vulns │

│ │

└──────────┬──────────┘

│

│

▼

┌─────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Send notification │

│ to Telegram channel │

│ (scan results) │

│ │

└─────────────────────┘

To change the approaches to scanning I was just simply changing the way which templates were used by nuclei to scan the hosts. For example for “Common Vulnerabilities” I was using templates like directory-listing or springboot-actuator. For this approach I was getting a lot of noise, usually when I reported those issues they were either OOS (out-of-scope) or they were duplicates. I ended up creating an exclude.txt file where I would keep a list of known issues so they would not get reported to the Telegram hook. In the end this approach resulted in pretty nice rewards but resulted in higher ratio of N/A reports and False Positives than other approaches.

For “Latest Vulnerabilities” approach I was running only templates that were recently added to template repository. It was a nice approach and I got paid for several issues found this way. It was also much less noise from these workflows as newest templates are not always a commonly occuring issues.

When it comes to “Random Vulnerabilities” I was surprised by how much true positive issues have been reported by this approach. I got several valid reports just by running random nuclei templates against buch of assets. So a takeway from this is that if you don’t know where to start your monitoring journey, scanning for random issues is always good 😄

I have also set up a dynamic fuzzing automation using wapiti but I have not yet get any meaningful results from this approach (apart from getting rid of DAST FOMO).

Part 5 - Was it worth it?

Now the interesting part, was it actually worth it? Because in the end it all breaks down to a summary of bills and the outcome if the automation was able to earn for itself. Total cost of the infrastructure used in the project was about around 17 USD per month, which rounds up to 205 USD per year when it comes to hosting costs.

On Hackerone, several open redirects, directory listings and XSS’s summed up to total of 550 USD. On Intigriti I was able to only land one report rewarded for 50 USD. On Yogosha, I reported several security misconfigurations which summed up to 830 USD. The best results I’ve had with Bugcrowd where I scored a nice XSS and several other bugs that were rewarded 2350 USD in total. So total result for whole year was 3780 USD. When you substract costs of the hosting the net earnings are 3575 USD. So was it worth it? Business wise, yes! I was able to get a nice side profit by just running a bunch of automation scripts and actively scan for vulnerabilities. However I think that the real reward for this project was actually learning how to do bug bounty automation at scale, how to solve unexpected problems that occured during development and how to optimize the scans to get the best value from the reports. I would encourage anyone interested in bug bounty to try this full-automation approach themselves as it is a great opportunity to learn new skills (and earn some $$$).

In the end I would like also to reflect on the fact why good vulnerability scanning automation is actually a hard thing to do? I think the answer comes from the multitiude of variables you have in the environment. Apart from rate limits, hardware limitations you have also a multitiude of approaches you can take. By far the most challenging parts I have to overcome when developing this project were:

- Choosing the right scanning methodology and realizing that you will never be able to scan everything,

- Optimizng the workflows so they yield reasonalby good results in finite amount of time,

- Reducing the amount of False Positives from vulnerability scans.